‘Only art and science raise men to the level of the gods.’

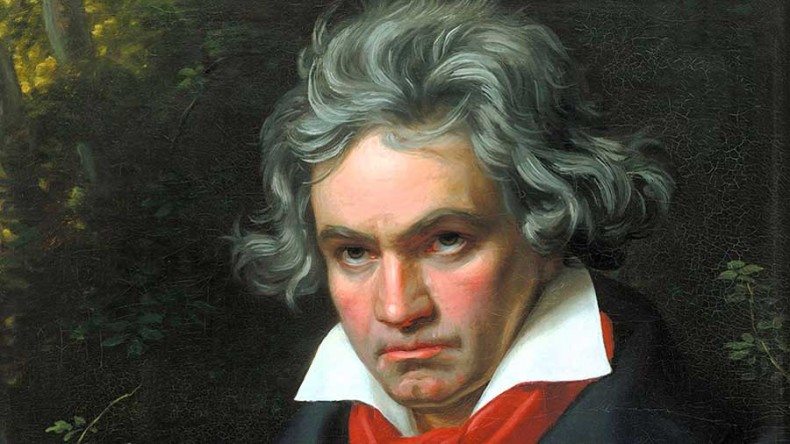

Few creative giants have risen to the spectacular heights of genius and artistic fulfillment as much as Ludwig van Beethoven. Beethoven’s ingenuity is legendary: his prolific works have sealed his place in history as a maestro of immense skill, blazing the trails of sheer musical prowess.

Popular culture has a peculiar habit of feeding into the myth of the tragic artist – through its association between creative genius and suffering – as seen in the case of Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Neruda or Edward Munch.

But perhaps nowhere is this mysterious link as present or acutely tragic as in the case of Beethoven. Despite his towering accomplishments, Beethoven’s life was marred by personal and professional tragedy. Beethoven suffered a difficult childhood, often at the receiving end of his father’s fury, enduring beatings as a part of his harsh musical training. These years of struggle were later ultimately rewarded by the bloom of his intellectual and creative accomplishment. The whole of Europe was awed by the extent of his genius, and in his own lifetime he came to command tremendous critical and commercial success.

And yet these happy circumstances were not to last long. In one of fate’s cruelest ironies, Beethoven began losing sense of his hearing by the time he was only twenty six years old, later becoming completely deaf. This would come to cast a life-long pall on the great composer, souring his relationships with friends and family, his income, and his own personal happiness. Deeply and profoundly affected by his loss of hearing, Beethoven was driven to the edge of perpetual despair, even coming close to suicide.

Which is why, this correspondence between him and a loyal fan is so extraordinary.The fan in question is Emilie M, an 8 year old girl and pianist in training, who wrote to Beethoven with admiration. She accompanied this letter with a handmade ‘pocketbook’ as a gift to Beethoven. In return, Beethoven responded with a letter of his own, which – in spite of his suffering and his indignity with fate’s vicissitudes – resonates with pure delight and joy.

This remarkable bit of historical correspondence, culled from the book Beethoven’s Letters – offers us a glimpse into the great artist’s mind, which – despite all its sadness – manages to leap beyond from the page, even today, into rising notes of infectious optimism, remarkable humility, and childish delight.

To EMILIE M

Töplitz, 17th July, 1812.My dear good Emilie, my dear friend!

I am sending a late answer to your letter; a mass of business, constant illness must be my excuse.

Your pocket-book shall be preserved among other tokens of the esteem of many men, which I do not deserve.

Continue, do not only practise art, but get at the very heart of it. This it deserves, for only art and science raise men to the level of the gods. If, my dear Emilie, you at any time wish to know something, write without hesitation to me.

The true artist is not proud, he unfortunately sees that art has no limits; he feels darkly how far he is from the goal; and though he may be admired by others, he is sad not to have reached that point to which his better genius only appears as a distant, guiding sun. I would, perhaps, rather come to you and your people, than to many rich folk who display inward poverty. If one day I should come to H., I will come to you, to your house; I know no other excellencies in man than those which causes him to rank among better men; where I find this, there is my home.

If you wish, dear Emilie, to write to me, only address straight here where I shall be still for the next four weeks, or to Vienna; it is all one. Look upon me as your friend, and as the friend of your family.

Ludwig v. Beethoven.

What is even more remarkable is the fact that Beethoven’s lament of the creative struggle – the gap between a person’s ambition and the actual quality of their output – is just as relevant today, amongst beginners and non-beginners alike. In fact, it poignantly finds an almost word-for-word echo in this remarkable advice from Ira Glass in this modern day and age.

For the first couple years that you’re making stuff, what you’re making isn’t so good, okay? It’s not that great. It’s trying to be good, it has ambition to be good, but it’s not quite that good.

But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, your taste is still killer. And your taste is good enough that you can tell that what you’re making is kind of disappointment to you. A lot of people never get past that phase, and a lot of people at that point they quit. And the thing I would just like to say to you with all my heart is that most everybody I know who does interesting creative work, they went through a phase of years where they had really good taste and could tell what they were making wasn’t as good as they wanted it to be.

They knew it fell short. It didn’t have the special thing that we wanted it to have.

Psst! Our free newsletter offers the greatest and the smartest ideas, essays, books and links in one convenient place. The emails you receive will be short, smart, and always interesting. Sign up here >>