A 162-year old publication that survived the Great Depression, two world wars, and the recession is losing out to new kids on the block. How did that happen?

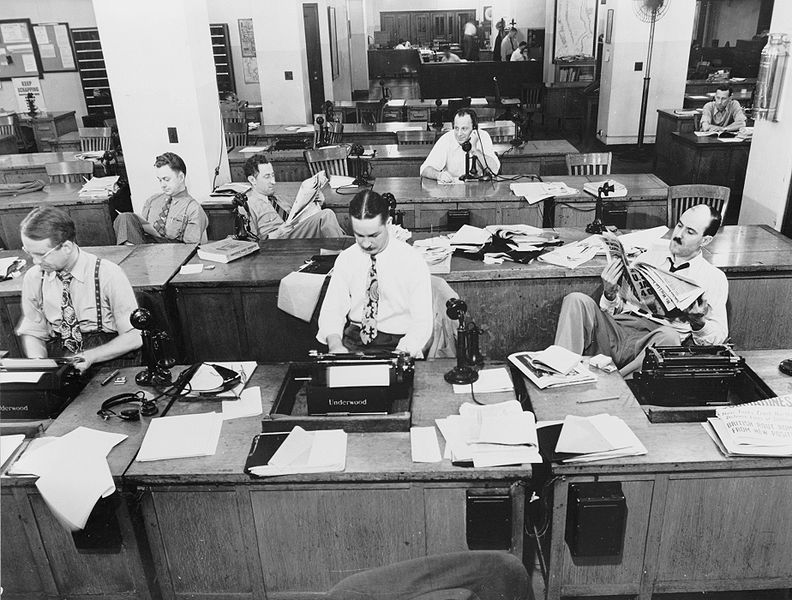

On a busy spring morning in March 2014, offices of The New York Times were abuzz with the usual torrent of activity. Phones were ringing off the hook, reporters were hammering away at their desks, and the steady click-clack of keyboards in the rooms and cubicles orchestrated a familiar, ever-present background noise. Across the floor, another battle of sorts raged. The New York Times’s top brass – including Arthur O. Sulzberger, Jr., Chairman of the New York Times Company, Mark Thompson, President and CEO, and Jill Abramson, the now-ousted executive editor – were all huddled together in the newsroom with The Times’s topmost editors and executives. The team had assembled over a monumental and overbearing question of importance: the future of The New York Times.

As the top personnel took their seats, a special, 97-page long report prepared by The Times’s topmost management and editors set the agenda for the meeting. It began:

“The New York Times is winning at journalism. Of all the challenges facing a media company in the digital age, producing great journalism is the hardest. Our daily report is deep, broad, smart and engaging — and we’ve got a huge lead over the competition.

“At the same time, we are falling behind in a second critical area: the art and science of getting our journalism to readership…we haven’t done enough to crack that code in the digital era.

“This is where our competitors are pushing ahead of us. The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal have announced aggressive moves in recent months to remake themselves for this age. First Look Media and Vox Media are creating newsrooms custom-built for digital. The Guardian and USA Today have embraced emerging best practices that have helped grow readership. And Huffington Post and Flipboard often get more traffic from Times journalism than we do.

“In contrast, over the last year The Times has watched readership fall significantly. Not only is the audience on our website shrinking but our audience on our smartphone apps has dipped, an extremely worrying sign on a growing platform.

“Our core mission remains producing the world’s best journalism. But with the endless upheaval in technology, reader habits and the entire business model, The Times needs to pursue smart new strategies for growing our audience. The urgency is only growing because digital media is getting more crowded, better funded and far more innovative.

“…We have watched the dizzying growth of smart phones and tablets, even as we are still figuring out the web. We have watched the massive migration of readers to social media even as we were redesigning our home page. Difficult new questions will arrive with each new shift. In all likelihood, we will spend the rest of our careers wrestling with them. ” [1]

How The Mightiest Can Fall

The New York Times’s history goes back over a period of one hundred and sixty two years. It was officially founded on September 18, 1851, by Henry Jarvis Raymond, a journalist who had earlier worked at The New York Tribune and Enquirer. [2] Long called America’s ‘newspaper of record’ for decades, the newspaper has earned the distinction of being counted amongst the world’s most respected publications.

In its inaugural issue, The Times outlined its founding vision and principles, in an endearing address to the public titled ‘A Word About Ourselves’. [3]

A WORD ABOUT OURSELVES

“We publish today the first number of The New York Daily Times, and we intend to issue it every morning (Sundays excepted) for an indefinite number of years to come.

“We have not entered upon the task of establishing a new daily paper in this city, without due consideration of its difficulties as well as its encouragements. We understand perfectly that great capital, great industry, great patience are indispensable to its success, and that even with all these, failure is not impossible.

For an organization that, even then, acknowledged that ‘failure is not impossible’, the acknowledgement has rarely held truer than it does today, with a dauntingly changing media landscape and an industry in turmoil. Even as The Times wrestles with the difficult new questions wrought on by the digital era, more and more blogs and publications spring up on the Web every day. The web is an ever-changing landscape, shaped by emerging trends, pop-culture, and an intersection between the makers and the consumers. Unlike in the traditional media models like radio, television and print, both the creators and consumers of content dominate online. By its very nature, the Web fosters creation, collaboration and consumption. Barriers to entry are the lowest they have ever been. Anyone with an internet connection and a smartphone can publish a book, release an album, or create the next big competitor that is the stuff of The New York Times’s nightmares.

So how could a giant like The Times have fallen so far and so hard? With all its enduring legacy and history, how could the Grey Lady, of all the publications in the world – have dropped the ball? Even with the weight of some of the smartest minds and industry titans on its shoulders, it is almost inconceivable that a 162-year old publication that survived the Great Depression, the two world wars, the financial crisis of the 80s and the economic recession of 2008 and onwards, is losing out to new kinds on the block.

How The New York Times Missed the Boat

To understand The New York Times’s current predicament, we must rewind the clocks twenty years ago.

The year is 1995. The web, previously a bastion of academics, scientists and military personnel has finally catapulted into the mainstream. Although still throttled by painfully slow speeds and limited infrastructure, the internet is about to change everything. Amazon is just getting started and is a nobody, Microsoft is still king of the Valley, Apple is down in the gutters and is on the verge of bankruptcy, and Google doesn’t exist. Facebook has yet to be a twinkle in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye.

On a frosty December afternoon in the glass offices of Manhattan’s plushiest office building, Martin Nieselholtz is talking to Arthur Sulzberger, the Chairman of The New York Times company. Nieselholtz has just been hired six months ago and put in charged for launching The Times’s website. He is in charge of The Times’s digital operations, which is previously wild and unchartered territory for the newspaper.

Sulzberger and The Times’s management wanted to put The New York Times on the web as-is, that is to say, they wanted to offer The New York Times just the way it was, except in electronic form. Nieselholtz disagreed, and said that they ought to try something radically different. He argued that merely putting the newspaper online was not enough: the company needed to take a cue from Yahoo! News, CNN, and the online news portals that were taking a unique approach to content and were growing more popular every day. In an interview with Riptide, Martin details his thought-process at the turning point in The New York Times’s history. Martin’s statements give an insight into exactly when and where The New York Times went wrong:

My thinking was, The New York Times should maybe approach the web, in some ways, the way Yahoo did. Yahoo was a directory. What The Times wanted, for good reason in some ways, was to publish the journalism of The New York Times on the web.

I think that, certainly, publishing the newspaper on the web is what was expected. It’s what the consumer expected. It’s what was logical. It was low risk, in many respects. It didn’t cost very much because we already had the content. It made a world of sense.

But, in some ways, some fundamental ways, it kept The Times from truly being a great innovator because it didn’t allow for something startlingly new.

We would not be competing with other newspapers. We would be competing with a whole range of providers. And CNN had already come on and was doing a very good job. It had breaking news in its DNA. It was writing short form, very pithy, good articles for the web.

Remember, it was a desktop world, small screens, not very much resolution, slow modems, narrow band connectivity. You’re talking about a user experience that is, in comparison with today’s user experience, pretty clunky. CNN had done a pretty good job, mapping the content to that user experience. They, in my view, set the bar on the news side.

Now, there were a lot of people who felt that the content was not as deep, or as analytical, or as interesting, as New York Times content. I would agree. It was very difficult to read long form New York Times articles on a screen at that time. It’s become much more comfortable to do with an iPad or even a modern display device, but at the time, it was really clunky.

We were colliding, now, with a range of media competitors, not just newspapers anymore. [4]

This, more than anything else early on, was NYT’s biggest misstep in losing its mojo in the face of new media. NYT failed to innovate on their strategic focus. Instead of thinking how the web itself would change the way content was read, distributed and produced online, NYT opted for tunnel-vision. Martin was right in assuming that NYT was competing with not just other newspapers – but with a range of media competitors. Unlike CNN, who adapted their content to short, easily digestible and shareable stories on the web; or Yahoo, who pursued portal-segregated news from the start, NYT didn’t fundamentally alter their content strategy to accommodate the user experience online. Simply taking the news stories on the web wouldn’t ensure that they would work as well on the screen as they did on paper.

Sharing these concerns with Sulzberger in 1995, Martin requested funds to form a new R&D unit, one solely dedicated to innovating a web-native strategy for NYT in the digital sphere. [5] Martin’s request was denied, and the website launched in 1996 with its strategic focus severely ill-adapted and not fully equipped to deal with the challenges of the new medium.

The Challenges

It is tempting to speculate how different things might have been had Martin got his wish. However, that is not to say that NYT didn’t catch on in the wake of more digital developments later on.

The company launched its first smartphone app for the iPhone in 2008. Successively since then, they have continued to launch more apps for other platforms and today they have one each for Android, iPad, Kindle Fire, and Windows Phone.

Fundamentally challenging to NYT is its elusive grip on expanding its audience. The Times has tried time and again to reach out to new demographics to extend its subscriber base. To that end, it has launched and marketed the new mobile and tablet apps for the younger, hip audiences. However, as with most things, the young and hip audiences are one step ahead: today, for many readers, their news habits span stories shared on Facebook, Twitter and other social media. In other words, the news comes to them not through search, but through social. Many millenials question, understandably, why they should pay $8 over a dedicated news app when they could read stories for free in their browsers from a multiple set of sources.

A New Strategy

As detailed in its innovation report, The Times identifies four key areas for its renewed strategy online These are: mobile offerings, social media, global reach, and video. [6]

Products: Niche Content

Close on the heels of its users’ changing habits, NYT has recently come up with a slew of dedicated offerings, mainly with niche apps and sub-sites. [7] These apps and site sections take a specific approach on the larger content available on the NYT site, and package them to audiences in smaller bytes. Examples

- First Draft a news politics site and newsletter specially for

- NYT Cooking app: an iPhone app offering a collection of recipes and culinary content from the NYT marketed as a niche cooking

- Times Premier: a ‘Behind the scenes’ offering that gives readers a sneak-peak into expanded content with e-books, ‘TimesTalks’ videos of journalist interviews (equivalent of DVD extra features).

- NYT Now: A standalone app, different from the NYT app, that is marketed as ‘Stories at the speed of life’. It catalogues NYT stories handpicked and summarized by editors, but does not give unlimited access to NYTimes.com

- Times Minute: a 60-second video offering from national and international news, politics and ideas on the NYT website

- Special Election App: delivering election stories and political developments

- Times Journeys: an “educational travel program” that connects readers with NYT journalists in their travels

- The Collection: A fashion app for iPad, which aggregates all fashion journalism from NYTimes.com, the Moment and T Magazine.

Video

Its video offering is led by Rebecca Howard, the GM of the Video Department. Howard has since added 17 new employees to the department and has said that it is working on original series, weekly web episodes, documentaries, and supporting videos for important articles.

Expanding the International Reach

The Times is putting significant effort into expanding its international readership. Perhaps the most significant shift towards this trend has been the rebranding of the International Herald Tribune, which NYT rechristened as The International New York Times. The international reporters now report directly to New York. [8]

Shedding Assets

Wrought on by Arthur Sulzberger’s call to ‘Invest in the Core’, NYT has sold a significant amount of its assets, both digital and non-digital in order to expand and fund its core operations. The most significant of these assets is the sale of regional newspapers: NYT sold its Regional Media Group in December 2011 , to Halifax Media Holdings for $143 million in cash. [9]

Also cases in point are the sales of About.com, which NYT sold to InteractiveCorp for $300 million in 2012, its stake in the baseball team, Boston Red Sox for $117 million in July 2011 and The Boston Globe to John H. Henry for $70 million in August 2013.

The Great Pay Wall of New York

In order to aid its flagging online revenues, The Times introduced a significant point of departure in its online strategy: the establishment of a paywall. Introduced in 2011, the paywall made the site content to readers for free only upto 10 articles per month. After that, readers would have to subscribe either in print or digital to NYT to be able to access its content.

The Competition

At first blush, it may be hard to believe that NYT’s serious competitors include sites such as Buzzfeed, which specializes in notoriously viral content through the form of picture posts, gifs, quizzes, and listicles (articles, in lists). Typical examples of Buzzfeed content include: 16 Signs You Grew Up Eating Health Food Before It Was Cool, What Pop Stars Looked Like When They Released Their First Album, 13 Everyday Awkward Moments, and 24 Of The Most Intense Facial Hair Styles You’ll Ever See. This may be tantamount to outrage for journalistic traditions, and some self-respecting journalists might even scoff at the idea of Buzzfeed being a serious competitor to NYT, calling it a professional sacrilege.

However, NYT makes it very clear in the internal report that they take Buzzfeed very seriously: ‘today, a pack of news startups are hoping to “disrupt” our industry. By attacking the strongest incumbent — The New York Times. How does disruption work? Should we be defending our position, or disrupting ourselves? And can’t we just dismiss the BuzzFeeds of the world, with their listicles and cat videos?”

The Times was very clear on its answer: No, they could not.

Conclusion

The future of The New York Times hangs on how well they continue to adapt to the changing habits of their readers. If their string of recent innovations is anything to go by, it is safe to say that The Times has learnt its lesson form the 90s. As long as serious and quality journalism is respected, The New York Times will survive.

Psst! Our free newsletter offers the greatest and the smartest ideas, essays, books and links in one convenient place. The emails you receive will be short, smart, and always interesting. Sign up here >>