A look at science fiction’s cult classic, and the ideas it espoused.

Robert Heinlein is one of science fiction’s finest. His work is richly imagined, beautifully written, and provoking for his time. Any Heinlein fan knows that Heinlein in on top of his game when it comes comes to plot development. But Heinlein has so much more to offer: he integrates a systematic and unique philosophy in his writing. At his intellectual best and his most provocative, Robert Heinlein is formidable.

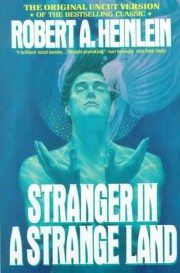

This is nowhere more apparent in Stranger In A Strange Land, his landmark 1961 novel that has come to be associated as one of the finest sci-fi novels over the decades.

The concept of a Martian – a human being by birth, but in essence, a Martian -rehabilitated on Earth is an arresting idea – a rich canvas. In Stranger In A Strange Land, this canvas is mainly coloured through lens of social commentary and a new moral philosophy that became a manifesto for the counter cultural movements of the 60s.

Although divided in 5 main parts, the novel can really be said to be composed of halves. The first half is where the narration is the focus, the story keeps moving and there is a real sense of ‘happening.’ The second half lags in terms of action but brings out the core concepts and ideas of the novel in full, successively developing from satire, taking on government and civilisation, to the formulation of a new philosophy which undermined the beginning of the Free Love movement that came in later in the decade.

Core Ideas of Heinlein’s Philosophy

Typically, Heinlein employs the use of two main characters as the main propagators of his thought and ideas. They are, of course, Jubal Harshaw and Mike himself.

Jubal, doctor, lawyer, and all-round cynic, contrasts strongly with existing social mores of the time this book was written in. He is, of course, libertarian; a ‘keep your nose in your own business and let other people keep theirs in their own’ sort of person. It’s no wonder that one of the many quips and aphorisms Heinlein accorded to him runs, ‘*A desire not to butt into other people’s business is at least eighty percent of all human “wisdom*.”‘

Sex

The core of Heinlein’s philosophy lies in sex – how sex is perceived, and ought to be perceived amongst humanity. When Mike, the man from Mars discovers that human beings share something that has no equivalent in the Martian culture, he is fascinated. On Mars, there is no distinction of ‘male’ and ‘female’ as such. The female equivalents are mere ‘nymphs’, who, by any accounts, do not figure into much prominence. However, as Mike discovers, things are different on Earth. Men and women co-exist. The male and the female are distinct, yet harmonise with each other. Sex is the basis for this harmony, the basis for all humanity. Sex is important. Sex is good. Mike discovers sex, and he is thrilled. More importantly, he is changed.

This is where Heinlein goes a step further for his time; his attitude towards sex in belief and practice were radically different from existing social norms for his time. To Heinlein, and consequently Mike, sex is not a commodity, to be hoarded and practised in the privacy of two individuals behind closed doors. Instead, sex is shared goodness, to be given and taken and exchanged at large. Where Mike comes from, jealousy as a concept does not exist. This lack of jealousy, lack of possessiveness manifest themselves in his attitude towards sex. Because jealousy doesn’t exist, polygamy is no problem.

Jubal explains Mike’s philosophy in contrast with religious indictments. The Bible declares: Though shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife. But this, as Jubal wryly observes, is a natural impossibility. As long as men continue to live, they continue to be subject to their desires, whether physical or otherwise.

For Mike, sex isn’t off-hands and restricted between two people. Love and sex, intertwined as they are, deserve to be shared among people, their goodness shared across all people in the Nest.

Far from something to be ashamed of or to be guilty about, sex is a goodness, to be cherished and enjoyed and shared.

Of course, this is almost a line-by-line blueprint of the hippie movement that came in later during the 60s. This book was published much before it happened, and was there just at the right time when it did. The Free Love movement of the 1960s underscores Mike’s philosophy.

Heinlein’s Thesis of Religion

While everyone was busy having orgies, it did not escape Heinlein to incorporate commentary on religion as well. This he does through the portrayal of the religious order, the Fosterites, who are of the Christian denomination but differ widely in essentials. While Christians unnecessarily torment themselves with original sin, Fosterites embrace it, accept it, and get ready to put it behind themselves. The ultimate aim of life according to Fosterites is to be happy.

Heinlein criticises Christianity’s doublespeak. Christianity and Islam are quick to mete out judgement to their followers, to dictate moral, social, political and sexual rules and judgments to their followers. Yet, at the same time, their scriptures are full of inconsistencies and sexual deviance. A case in point in Lot’s offering of his two virgin daughters to a mob banging on his door. Lot trades his young daughters so as to have ‘the mob stop banging on the door.’ This is the God who complies with such an act, who rewards this morality while simultaneously frowning upon a million other things. Such a God is a hypocrite.

Fosterism then, as a religion seeks to eliminate this bias, to do away once and for all with the doublespeak and hypocrisy of religion. However, their unabashed glorying in happiness and hedonistic pleasure is initially disquieting to Jubal and Jill, who of course does a complete back flip in the latter part of the book.

Thou Art God

With the new creed of sex as ‘growing closer’, as a part of Mike’s new religion, another creed emerges. ‘Thou Art God’ is a summation of Martian attitude towards God at large and how He related to the Universe. To grok God is to grok the Universe in full. To grok existence itself, for God is in you and the person next to you and everything else above and below the Earth and under the sun. If nothing else, science fiction is always going to be grateful to Robert Heinlein for giving us this word.

The Christ Parallel

Mike’s choice to usher in a new thought and mode of belief in the world, and his subsequent sacrifice to that end are an unmistakable nod to the story of Jesus. It’s in fact a tale that is a direct allegory to the life of Christ. Like Jesus, Mike is born to a set of parents not including the husband as the biological father. Like Jesus, Mike observes a system of thought and belief in a world gone wrong, and, like Jesus, he wishes to bring in a new way of living that would usher in happiness for in the world and all its people. Like Jesus, Mike is ultimately doomed to sacrifice and a bloody end.

Grokking

The most important concept in the book by far is the idea of ‘grokking’. To grok, literally, means to ‘drink water’. But used in the sense it is used so often in the book, it means to understand – intuitively, emphatically. To grok is to understand, comprehend, empathise – to such an extent that both the observer and the observed become one. You cannot grok without becoming one in unison with the one grokked.

Conclusion

Stranger In A Strange Land provoked and outraged and shocked people of its time – it still does today, in certain places and among certain people. However, half a century on, the novel does not age quite so well as a sci-fi novel. Any hope of life on Mars, our direct neighbour, let alone a civilisation as highly advanced as the one portrayed in the novel, in light of successive Martian expeditions over the decades is rendered unrealistic at best.

There are also plenty of flaws with the book, most particularly Heinlein’s portrayal of women. Women are either shown as passive and ‘go-along-with-what-he’s-saying-and-doing’, like Miriam, Dorcas and Anne, or manipulative and controlling, like Mrs. Douglas and Patty and, to some extent, Jill. Not to mention Jill saying, ‘Nine out of ten times, when a woman gets raped, it’s her own fault.’

It is also very preachy at certain points, with Heinlein having his main characters chiding the other lesser mortals that inhabit the book for not having the same brilliant ideas as their own. The novel, while taking off brilliantly at a fast pace in the first half of the novel, completely slacks and lags in action in the second half, when the philosophy takes a backseat to the story.

However, all these things considered, the redeeming hallmarks of Stranger are perhaps its social commentary and its original ideas about religion and civilisation, which, in the post-60s, post-hippiedom world might strike us as tired and tested, but which were strikingly original and timely for the time it was published in.

Psst! Our free newsletter offers the greatest and the smartest ideas, essays, books and links in one convenient place. The emails you receive will be short, smart, and always interesting. Sign up here >>

I loved your summation and interpretation of one of my favorites by Heinlein. Thank You so much! Despite the dated science, it remains, in my opinion at least, a timely book even today in that it questions conventions and philosophies which have are still deeply entrenched in 2018.